Research Spotlight: Literacy Success Using Reading Eggs

Synopsis: Measuring Reading Eggs' Effectiveness

During the 2016–17 academic year, Latisha D. Lowery, Ed.D., conducted a study to examine the effects of a technology-based reading intervention program, Reading Eggs, on elementary reading growth. Lowery (2017) recruited two classrooms of 2nd graders at Fairfield Magnet School for Math and Science (FMSMS) in Fairfield County School District, located in Winnsboro, South Carolina, to participate. One group, in addition to teacher-delivered intervention as usual, received a supplemental Reading Eggs intervention for a minimum of 60 minutes per week for a six-week testing period.

This action research study used quantitative data from weekly progress reports within Reading Eggs combined with pre- and post-assessment scores from The Fountas & Pinnell Benchmark Assessment System 1, which offers a growth scale of reading ability, to determine effectiveness.

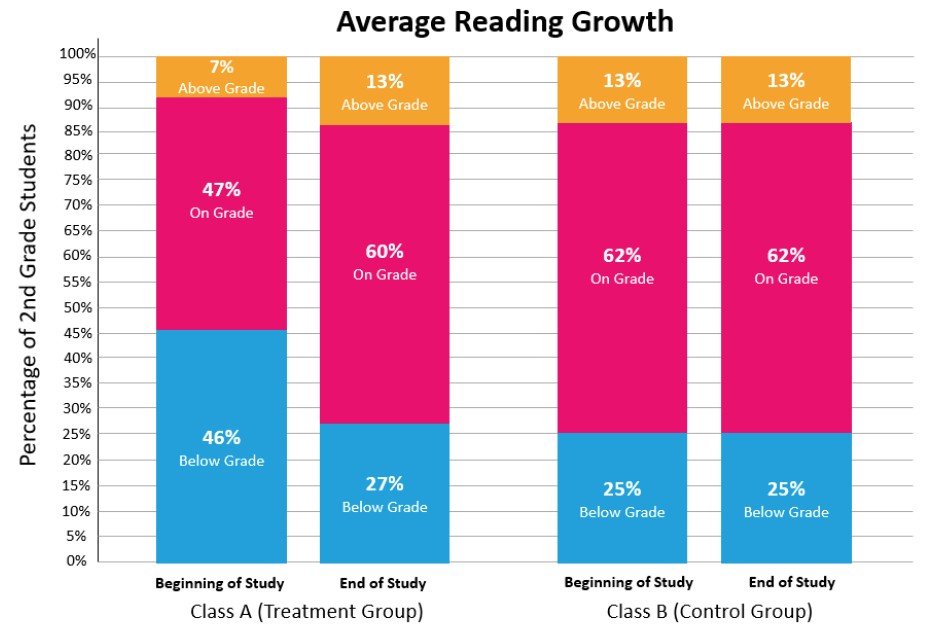

After the testing period, the author's results revealed that the Reading Eggs program, when used as a supplement, was effective in improving reading proficiency scores. The percent of below-grade students in the Reading Eggs treatment group decreased by 19% over the course of the study, while the percent of children below grade in the control group remained the same.

The table above represents Lowery's 2017 findings as recorded on pages 44–45 of the action research study. Each class's average reading growth was reviewed using scores from The Fountas & Pinnell Benchmark Assessment System 1 at the beginning of the six-week study and again afterwards.

The Challenge: Reading by the Third Grade

The research site examined in Lowery's 2017 study was Fairfield Magnet School for Math and Science (FMSMS), a small, rural, Title I school in Winnsboro, South Carolina. FMSMS serves a primarily African American population of nearly 400 students in prekindergarten through 6th grade. As noted by Lowery (2017), at FMSMS, foundational literacy is emphasized to ensure that all students are proficient readers by the third grade according to the South Carolina Read to Succeed Act of 2014. In hopes of closing the reading achievement gap, FMSMS developed a kindergarten intervention program that allows struggling readers to work with a certified reading interventionist for 30 minutes daily.

Lowery (2017) stated that, for students in 1st and 2nd grade reading, interventionists were not available. Classroom teachers have a minimum of 30 minutes each day to provide reading intervention, but “Due to the varied reading levels and class sizes, teachers are unable to work with each student every day” (Lowery, 2017, p. 30). Using Fountas and Pinnell's (2012) research on guided reading and the reading benchmark assessment system, teachers at FMSMS pre-assess all students and group them according to their reading proficiency levels. Then, to address the specific individual needs of 1st and 2nd graders, when students are not able to work in a one-to-one or small-group setting with a certified educator, Reading Eggs is implemented.

How They Did It: Action Research Quantitative Study

Determining the success of Reading Eggs as a supplemental reading intervention was paramount to ensuring that all K–2 students were supported at their individual level to meet proficiency expectations by the 3rd grade.

The action research study compared the achievement levels of students over a six-week period from September 2016 through October 2016, during which time 31 second grade students were studied. Class A (15 students) was the treatment group, while Class B (16 students) became the control group. The author noted that both classes' teachers planned together and that the instruction closely aligned to one another. Students were given 30 minutes each day in which Reading Eggs was made available, with each individual child completing a minimum of 60 minutes per week in the program.

When students work in Reading Eggs, they are presented with self-paced instruction, practice, and assessment that is at their level. Following a short placement test, students complete sequenced lessons that include 6 to 12 activities covering skills that expressly address the five pillars of reading—phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension.

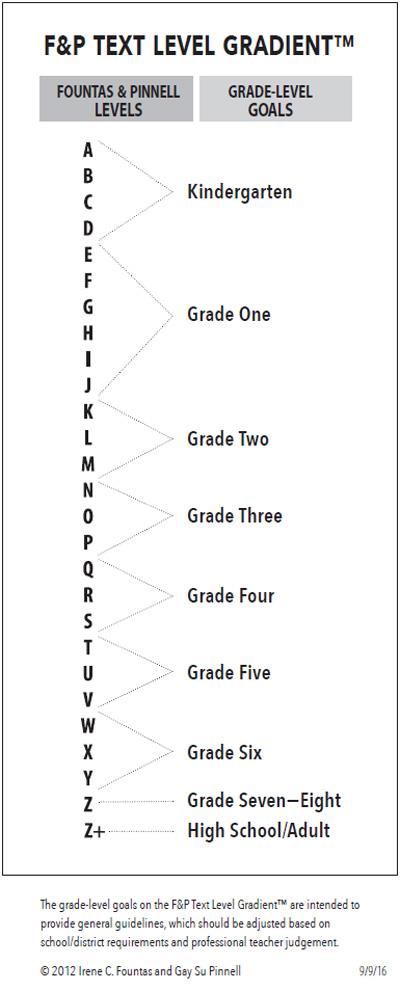

To benchmark learning at the beginning and end of this study, Lowery used The Fountas & Pinnell Benchmark Assessment System 1. “[This] is a one-on-one assessment tool that is used to identify the instructional and independent reading levels of students. The assessment system uses a text level gradient ranging from level A–Z+ or kindergarten through eighth grade” (Lowery, 2017, p. 41).

Lowery (2017) noted, “Based on the Fountas and Pinnell (2011) text level gradient [for independent reading levels], students entering second grade should be on a Level J to meet the benchmark requirement. . . . Moreover, by the mid-year point, the benchmark is Level L, and at the end of the school year, students should be reading on a Level M (Fountas & Pinnell, 2011)” (p. 42). “Additionally, progress reports from the Reading Eggs program [were] used to allow for continuous progress monitoring of the students receiving the supplemental intervention treatment” (Lowery, 2017, p. 9). These reports detail lessons completed, lessons mastered, and individual learner strengths.

Achieving Success: Effectiveness of Reading Eggs on Elementary Literacy Growth

In comparing reading growth across both classes, Lowery (2017) concluded, “It is evident that the teacher provided interventions are effective in improving reading proficiency levels as determined by [The Fountas & Pinnell Benchmark Assessment System 1(2011)]” (p. 45). However, Lowery noted, “Since Class A's students showed more growth than Class B, it is clear that targeted, needs-based reading interventions have a positive effect on reading proficiency levels” (p. 46).

Based on the data collected from this action research study, students who were given supplemental reading support using Reading Eggs showed more overall growth than the students who did not receive support (Lowery, 2017, p. 45).

In Lowery's study (2017), “At the beginning of the 2016–17 school year, 32%, or 10 out of 31 second grade students, were not reading on or above grade level” (p. 33). After the interventions and the Reading Eggs supplement, Class A experienced a 13% increase in the number of students reading on grade level and a 6% increase in the number of students reading above grade level. In Class B, after the needs-based interventions only, the percentage of students in each reading category remained the same. When comparing both classes, it is evident that Class A demonstrated the most growth. “93% of the students in Class A increased by at least one reading level, opposed to Class B in which 19% of the students increased by at least one reading level” (Lowery, 2017, p. 46).

Turning Data into Action: Changing the Game in Literacy Intervention

According to Lowery (2017), moving into the 2017–18 academic year, leadership took steps to ensure that Reading Eggs was used with fidelity in all first and second grade classes. Teachers completed a two-day training in August 2017 to ensure that they could successfully set up accounts, monitor progress, and generate reports. In September, teachers administered the initial The Fountas & Pinnell Benchmark Assessment System 1 and began in-class interventions and supplemental instruction in Reading Eggs.

“The goal is to provide students with a minimum of one hour in Reading Eggs weekly. This supplement does not replace the small group intervention and one-on-one interventions that are already taking place in the classroom. Teachers will be expected to continue their daily practices of meeting with students during guided reading and with students in one-on-one settings. Teachers will be expected to progress monitor and take anecdotal notes in their data notebooks” (Lowery, 2017, pp. 55–56). Students will continue to be reassessed using The Fountas & Pinnell Benchmark Assessment System 1, and data will be compiled and analyzed before further instructional decisions are made. “Action research is cyclical, and it is our goal to continuously improve instructional practices for the students at Fairfield Magnet School for Math and Science” (Lowery, 2017, p. 56).

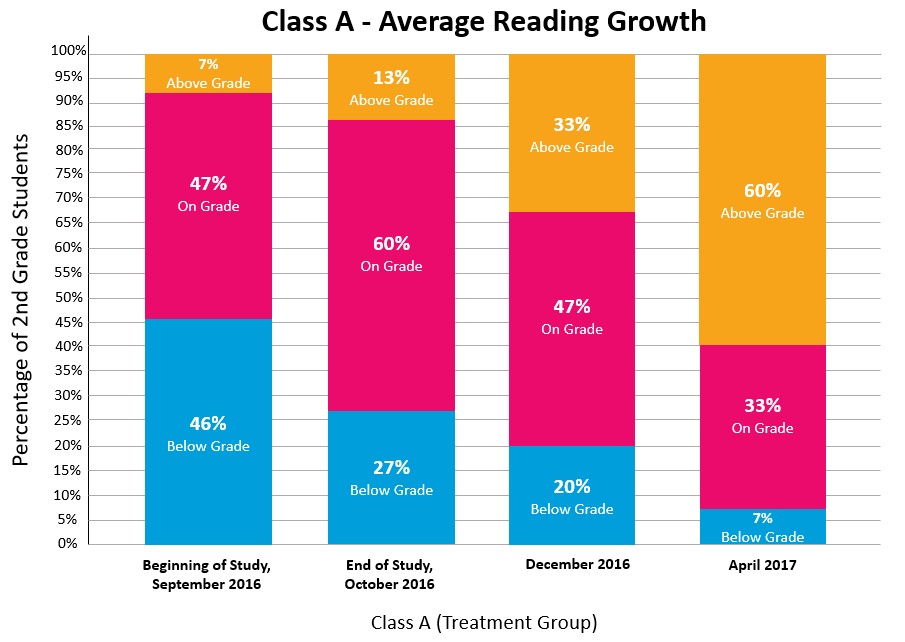

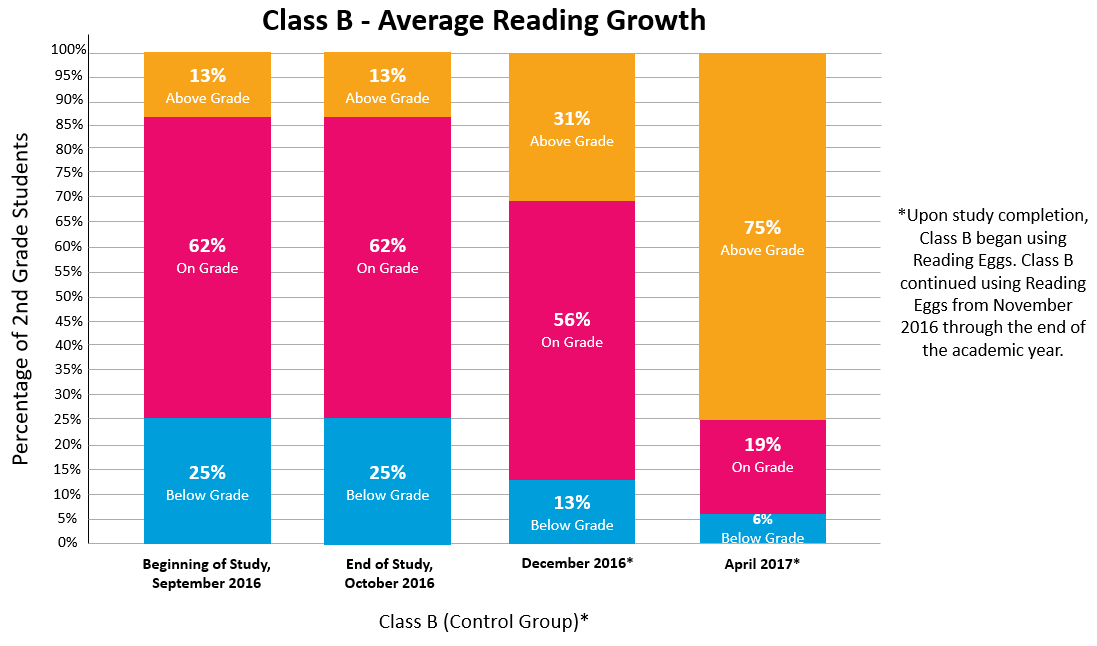

Tables below represent Lowery's 2017 findings from pages 63–66 of the research study. Each student's individual reading growth was reviewed in Class A (Treatment Group) and Class B (Control Group) as benchmarked by The Fountas & Pinnell Benchmark Assessment System 1.

Fountas, I. C. & Pinnell, G. S. (2011). Assessment Guide 1 (2nd ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Fountas, I. C. & Pinnell, G. S. (2012). Guided reading: The romance and the reality. Reading Teacher, 66(4), 268–284.

Lowery, L. D. (2017). Effects of Reading Eggs on reading proficiency levels (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (Publication No. 10265638)

Learn more about the Reading Eggs Scientific Research Base.